The best way to improve writing

Writing is like any other skill. The best way to improve is through deliberate practice. Ericsson et al. first defined deliberate practice in 1993 as purposeful and systematic practice with the goal of improving performance.1 I’ve spent substantial time thinking about the relationship between deliberate practice and writing. In this essay, I’m going to show how deliberate practice is critical for improving writing abilities.

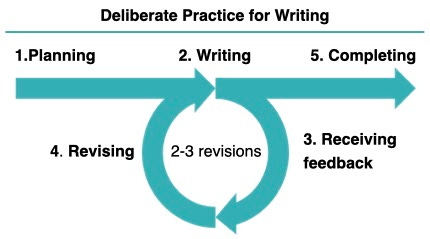

Before we begin, let’s first consider a high-level view of what deliberate practice steps look like for writing. A person begins with planning and then moves to writing. After completing a draft, they go through the receiving feedback and revising loop multiple times to continuously improve the writing before completing the work.

Admittedly, the diagram lacks the complex nature of deliberately practicing each step, which we’ll get into later. However, I like to use this simplified version to set up two critical concepts we’ll keep coming back to throughout this essay and future writing.

Coaching: People need support at each step of deliberate practice. This is the same as having a great sports coach, music teacher, or educator. The better the coaching someone receives, the better they will be at a skill. The coaching concept also ties with Bloom’s (1968) 2 Sigma Problem where an average student tutored one-to-one using mastery learning performed 98% better than an average student in a control class.22

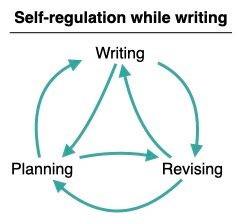

Self-regulation: Self-regulation strategies are guided by metacognitive skills (thinking about one’s thinking). The strategies are recursive, where writers flexibly switch between the planning, writing, and revising processes. They allow people to perform deliberate practice independently by monitoring and evaluating their own writing and thoughts at each step. Building self-regulation skills for writing greatly improves outcomes. For example, Self-regulated Strategy Development (SRSD) for writing planning has had an average effect size of one across more than one hundred studies, meaning students perform one standard deviation better on average than a control group.3

Coaching and self-regulation go hand in hand. Some people build self-regulation strategies on their own; however, I believe the vast majority of people struggle to identify and build these strategies without individualized coaching. Coaching also continues to build new self-regulation practices on the foundation of old ones, continually introducing more and more complex strategies as a person becomes a better writer. The most esteemed writers in the world all have great coaches (e.g., editors).

My formative writing experiences

I often dislike myself as a writer. I often struggle to clearly get my thoughts on a page (or screen). It frustrates me. As I’m writing this, I know I need to go back to everything I’ve already written to improve it. It’s just not clear! However, I’ll leave it to a future essay to walk through my writing and revising process. Now, why am I telling you about my struggles? It’s to lead into an exercise. I want you to think about your experiences where you found yourself rapidly improving your writing skills. I’m going to go through this exercise now.

AP European History. Mr. Bekemeyer had a profound effect on my writing. He beat structure into me. He pushed hard on content, structure, reasoning, and clarity. I often got a B or C on a first draft (first draft As were rare). I then revised using his feedback until I got an A. Sometimes, it would take four drafts.

McKinsey. I first realized I was a terrible writer when I started at McKinsey. I joined after graduating from MIT and spent over four years improving my writing skills. First, I went through training on how to plan and structure a document. Then, I received feedback on my planning and writing on a daily basis from other McKinsey consultants. I also experienced how the audience (clients) responded to the documents to better help revise and structure my thinking. The PowerPoint writing I did also helped me synthesize my thoughts into headlines with supporting evidence, determine what was important, create coherence in my arguments (i.e., the flow of logic from slide to slide), and forced me to be exceptionally concise (e.g., the space limitations of bullet points).

Writing a book. I decided to write a book in 2013, Embrace the Case Interview. The purpose was to help aspiring consultants be more prepared when interviewing. Writing a book built many of my self-regulation skills. I was continuously monitoring what I wrote and making adjustments, often because I was unhappy with the flow of the logic within and across chapters. I probably revised each chapter at least five times, and my older brother was kind enough to provide feedback (often tearing my logic or structure apart). The result was 347 pages and about 2,000 books sold to date.

Starting Prompt. Jordan, John, and I started Prompt in 2014. We initially provided all of the writing feedback ourselves. This process greatly helped me build mental models for dissecting other people’s writing and understanding how I could coach people to improve as well as how I could train people to be coaches. I found my own self-regulation strategies for revising my own writing have immensely improved as I continue providing feedback to others.

Writing about Prompt. Today, I spend hours per week penning my thoughts on writing and analyzing sources. I find this process helps crystalize my ideas and enables me to more effectively identify strategies, design products, and speak about what we do in compelling ways. I rely on the self-regulation strategies for planning, writing, and revising that I’ve built up over the years. But, I still ensure I get feedback on my writing from my team and our advisors. For example, my co-founder, John, often rips apart the logic on the early drafts for my newsletter.

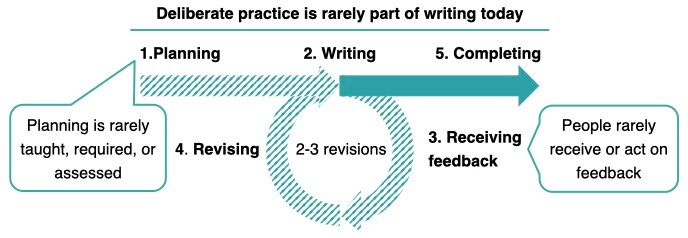

Now for some reflection. I cannot remember any profound effects on my writing from a K-12 or MIT educator other than Mr. Bekemeyer. I believe it’s because I did what most other students did. I just wrote and completed. I didn’t bother much with planning or revising. My instructors didn’t spend much time teaching planning. I rarely received meaningful feedback or revised my writing. I generally got a good enough grade, so I didn’t bother to change. I rarely cared about my writing until I started in the workforce. I had yet to understand the profound importance of written communication, and I couldn’t have cared less about Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales.

Every time I felt my skills dramatically improving, I was going through deliberate practice, whether I had a “coach” or I was using my own self-regulation strategies. I assume you and anyone else reading this have had similar experiences – you improved because you were deliberately practicing your writing.

Improving writing

The most effective implementation of deliberate practice leverages both coaching and self-regulation. The coaching is primarily applied in the planning and receiving feedback stages. It can also be valuable during writing and revising to teach self-regulation strategies to people who do not yet have these strategies fully-formed.

As alluded to earlier, the writing process is messier than the word “writing” seems to entail – there are recursive loops of self-regulation everywhere. Planning may occur at a higher level before putting fingers to keyboard or thumbs to phone; however, a writer is continually revisiting and adjusting the plan as they are writing. A writer is continually revising their words, structure, and thoughts. Writing with self-regulation has pathways everywhere – pathways writers often don’t even realize they’re taking because they are second-nature.

There are all kinds of self-regulation strategies to build. If given time, I can identify hundreds (or thousands) I use every time I plan, write, and revise. You would be hard-pressed to write a single word without using some ingrained self-regulation strategy. These include sentence-level self-regulation for grammar (e.g., subject-verb agreement) and syntactical fluency (e.g., varying sentence structures). These also include higher-order skills such as evaluating the accuracy of sources, synthesizing sources, identifying logic gaps, developing a structure, and attending to an audience’s perspectives.

Where we go from here

If you’re trying to improve your own writing, get a coach. Identify what self-regulation strategies are your strengths and where you need to improve. Spend time planning, writing, and revising. More broadly, if you’re reading this, you likely are a decent writer compared with the rest of the world. This is where things get tricky.

People need coaching and engaging in the writing process to build self-regulation strategies and improve their writing. Unfortunately, our education system and professional world are not structured to improve writing. Most students and professionals write and complete without planning, revising, or receiving feedback. People are rarely coached on how to plan their writing, and people rarely receive honest and effective feedback or act on the feedback they receive.

The result, based on my synthesis of many sources, is that only 1 in 10 people exit the US education system with adequate writing skills for the workforce. Anecdotally, this number is far worse as nearly every executive I speak with laments the state of their employees’ writing skills.

Now, you’re probably wondering, “how do we implement deliberate practice and fix writing in education and the workforce.” I have many thoughts, but we’re out of space for this week. Feel free to reach out if you want any sneak peeks of what’s to come.

Please subscribe to get weekly updates in your inbox (if you have not yet subscribed). Also, if you find value in my writing, please share it with a friend.

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406.

Bloom, B. S. (1984). The two-sigma problem: The search for methods of group instruction as effective as one-to-one tutoring. Educational Researcher, 13(6), 4-16.

SRSD Online – Home. (2020). SRSD Online. srsdonline.org.