Most people don’t know they’re bad at writing

Most people are bad at writing and don’t know it. Most good writers overestimate the abilities of poor writers. These gaps between perceived and actual abilities have immense implications for writing in education and the workforce. Students and professionals don’t realize they are poor writers because they don’t receive feedback. Leaders and educators who are good writers often struggle to identify the skills poor writers lack, and therefore, struggle to improve the writing of lower performers.

In this issue, we’re going to start by exploring why people’s perceptions of their writing abilities don’t match reality. Then, we’re going to discuss how to break this perception. By the end, you’ll have actionable steps for evaluating yourself, providing feedback to help those around you match their perceptions with reality, and building writing skills in yourself and others.

Writing and the Dunning-Kruger Effect

The gap between perceived and actual writing abilities is a classic case of the Dunning-Kruger Effect. People with low ability at a task overestimate their ability. People with high ability at a task underestimate their ability with respect to others, as they perceive other people as being better than the other people actually are.1

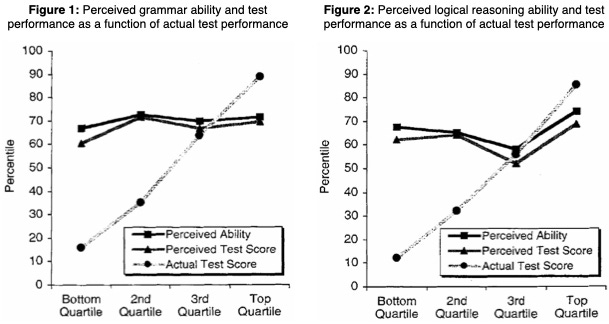

The Dunning-Kruger Effect is powerful. Let’s take a look at two writing-skill-related charts from the 1999 article Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One's Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments.2 The first is on grammar ability, and the second is on logical reasoning ability.

The magnitude of the gap between perceived and actual abilities is astounding. Students in the bottom quartile perceive their abilities as similar to the abilities of students in the top quartile. Students in the top quartile tend to be self-aware that they are skilled. However, they have a lower perception of their abilities than their actual abilities when asked to compare their abilities with the abilities of others. This is because top-quartile students perceive others as being more skilled than the others actually are.

Now, let’s apply the Dunning-Kruger Effect more directly to writing in education and the workplace, where there’s a significant gap between perceived and actual abilities. We find this gap is often compounded by educators and managers providing limited (or zero) writing feedback as they are strapped for time and want to avoid conflict. These incentives reinforce low performers’ belief that they are competent.

Students: No feedback + a good grade = students think they’re good.

We know actual student writing abilities are poor. 3 in 4 high school students score below proficient on writing. Only 3% of students are advanced.3

We know students tend to only receive positive indicators of their performance. In 2013, nearly 50% of university students in a given course received A’s, and the average GPA was 3.15 (compared with 30% and 2.85 respectively in the 1980s).4 Additionally, we know students rarely receive or act on feedback on their writing. When students do receive feedback, it tends to be surface-level (e.g., grammar) and is dismissed.5

Nearly everything educators do confirms the bias that students are better writers than they actually are. Let’s take a look at two examples to put the perception and ability gap in more context.

Example 1: In Prompt’s work preparing students for writing-intensive AP exams, we surveyed students and found nearly 3 in 4 had an A or A- in their class. Yet, when asked what they expected to receive on the exams, about the same number said a 3, which is equivalent to a B-, C+ or C in the college course.6 The students’ A grades provided a confirmation bias – that they are good. However, they were unable to evaluate their situation – the same work would generate a C grade in college.

Example 2: I vividly remember a snarky email I received from a student back when Prompt was testing a new service. We let students upload any assignment and receive a grade and two points of high-level feedback on their content and structure. The service’s purpose was to help people realize the gap between their perceived and actual writing ability (for free). I filled out the rubric, which resulted in a C+. The student replied, “Well, you can’t be right because I got a 94%.” I thought I was being nice; the essay didn’t even have a thesis statement and lacked a coherent line of thought. This is merely one memorable example of a pattern we see across education.

Professionals: No feedback + positive performance reviews = people think they’re good.

We know workplace writing abilities are poor. Employers believe only 45% of new college graduates have adequate written communication skills for the workforce, and only 57% have adequate critical thinking and problem solving skills.7 These numbers overstate writing abilities; the problem is actually far worse, as discussed in my essay, Writing is the Gateway to Critical Thinking. United States companies spend more than $3B per year remediating writing.8 I routinely hear corporate executives lament the state of writing skills among their employees. Yet, at the individual level, most people think they’re good.

We know employees rarely receive feedback on their writing.9 Think about the last time you received valuable feedback on something you’ve written. Think about the last time you provided detailed feedback on something someone sent you. I bet these are not frequent occurrences. If they are, think about colleagues you’ve had or companies you’ve worked at or with. Writing feedback is not the norm. Instead, the audience stalls or dismisses the thoughts because they are confused. The writer never sees the confusion and instead writes off a non or delayed response as being unimportant or a bad idea rather than due to poor writing.

Leaders and Educators: Only evaluating the result + limited time = you believe your team and students are better than they are.

How often do you give a task to someone and get back something you weren’t quite expecting? It’s probably almost always worse than you were expecting. Perhaps it just doesn’t seem well thought through, or it’s written in a confusing manner. Often, we just dismiss these situations. Perhaps we believe we must not have explained what we wanted well enough. Perhaps the person didn’t have the context or time needed. Perhaps you should have just done it yourself.

We often don’t spend the time required to analyze the root causes of poor results. If you are a strong writer, spending limited time evaluating the result likely leads to a Dunning-Kruger Effect. Even though you know the result is poor, your perception of the other person’s abilities is still actually higher than their abilities actually are. This is a critical problem you need to be self-aware of, or else any feedback you do provide will require too high of ability levels, making it hard for the person to implement.

When we spend the time analyzing a person’s writing process and results, we find surprising things that feel basic to “good writers” but cannot be assumed for poor writers. In writing, we often find students and professionals struggling with foundational skills, such as the sources skills of the Writing to Learn Framework presented in my essay, Learning Through Writing. Poor abilities with identifying, comprehending, synthesizing, and using sources can be underlying issues that go unnoticed and therefore unsolved. Without solving the underlying issues, it becomes impossible to improve the higher-order writing skills that present more clearly as a problem.

Breaking the “I’m a good writer” mindset

There is good news. It is possible to make people self-aware of their abilities and generate improvement. Kruger and Dunning manipulated a student’s competence by providing instruction in hopes of building metacognitive skills (thinking about one’s thinking). Upon providing the instruction, students were able to more appropriately judge their skills and even improve their abilities.10

For writing, closing the gap between perceived and actual abilities requires two things. First, students and professionals need to receive actionable feedback on their actual performance – not just a generalized score or comment but targeted improvements to make. Second, they need to receive instruction as the metacognitive skills required to produce writing are nearly identical to the skills required to evaluate writing. Instruction targeted at building self-regulation allows students and professionals to self-monitor and evaluate their own writing, which allows them to more closely match the perception of their abilities with their actual abilities, a prerequisite for improving skills.

Implications for improving writing

The first step to making people better writers is to make them aware that they have a problem. This is hard. No one likes to get feedback that they aren’t as good at something as they thought they were. This is why the feedback needs to be specific, actionable, and instructional. People need to receive instruction so that they build metacognitive skills they can use to evaluate their own writing.

Leaders need to understand that some people are far less skilled than they seem to be. The starting point from which we need to improve skills is almost always lower than we think. I’m often guilty of this as well. I provide feedback in ways I believe people can understand and learn from, but the person I provide feedback to may struggle to interpret the feedback and implement it appropriately. If I’m unaware of this problem, I may write it off to incompetence – i.e., the person just isn’t good or doesn’t get it. Instead, I need to be aware that my initial assessment of their abilities was incorrect. The feedback I provided may have assumed skills the person did not have. I can then solve for the root cause of their confusion so I can provide clearer instructions that match their abilities and generalize and transfer to their future work.

The first thing you should do is evaluate your own writing. Do your perceptions match your actual skills? Consider having a deep conversation with a colleague you communicate with frequently. Bring specific writing examples and ask targeted questions. What is the purpose of each piece? Where is the writing confusing? Why may someone not have agreed with it or acted on it?

Next, evaluate the writing of those around you (your students or team members). Consider the feedback you’ve provided in the past (if any) and evaluate if your students or team members have taken appropriate steps to generalize the feedback in their subsequent writing. Then, consider setting up a one-on-one with each person to talk specifically about writing. This will take some preparation as you’ll need to provide specific examples from a person’s writing and instruction on how they can improve. Your goal is to build awareness of the problem and put in place an improvement plan. This is time-intensive, but it will pay long-term dividends.

At Prompt, we build writing skills through deliberate practice, consisting of instruction, feedback, and self-regulation (see my essay, The best way to improve writing). We often find working with us is the first time students and professionals realize they are poor writers for the abilities required to meet their goals (e.g., getting into a specific college, landing a certain job, succeeding in their job, earning a promotion). Helping people understand they are bad at writing is the first step in helping them become better writers.

Please subscribe for more insights on writing in education and the workforce (if you have not done so already). Also, send one minute to share this issue with some friends, colleagues, or even acquaintances. We’re starting a “writing is important” movement. All are welcome!

Kruger, Justin; Dunning, David (1999). "Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One's Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 77 (6): 1121–1134.

Ibid.

NAEP Report Cards - Home. (2011). The Nation's Report Card. Nationsreportcard.gov.

GradeInflation.com. (2016). Grade Inflation at American Colleges and Universities. Gradeinflation.com.

Graham, S., MacArthur C. A., & Herbert, M. (Eds.). (2018). Best Practices in Writing Instruction, Third Edition. The Guilford Press.

AP exam scores - AP higher education - the College Board. (2020). Retrieved February 18, 2021, from aphighered.collegeboard.org/about-ap/scoring.

National Association of Colleges and Employers. (2019). (rep.). Job Outlook 2019. Retrieved from naceweb.org.

National Commission on Writing in America’s Schools and Colleges. (2006). Writing and school reform. New York: College Board.

Kruger, Justin; Dunning, David (1999). "Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One's Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 77 (6): 1121–1134.

Ibid.