What makes a writer good?

Writing signals intelligence and competence. Good writers are perceived to be intelligent and competent. Poor writers are perceived to be not intelligent and incompetent. In other words, reading something from a good writer leaves you thinking, “this is smart” and “this makes sense.” Reading something from a poor writer leaves you thinking, “I’m confused,” “this doesn’t make sense,” and “this person doesn’t seem to have thought this through.”

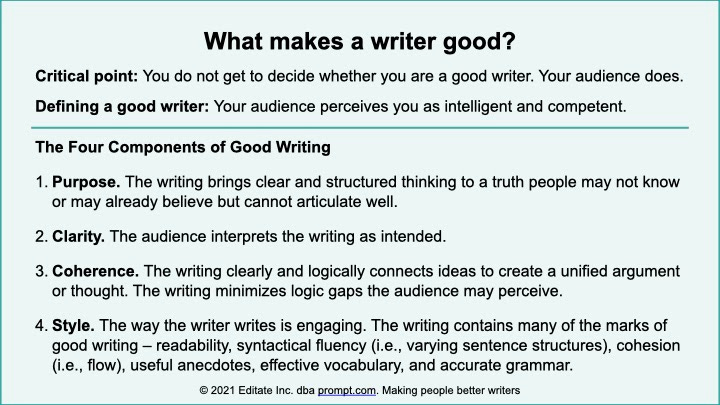

To be a good writer, you must be perceived as intelligent and competent. Why? It’s because...

You don’t get to decide whether you are a good writer. Your audience does.

Let’s go through a thought exercise. Who do you consider to be intelligent and competent? You base your perceptions of others on outward expressions of their intelligence and competence. These outward expressions tend to relate to how people communicate – their speaking and writing – or how others communicate about them – others’ speaking and writing. Communication is the only way for us to create an opinion of someone.

What about your writing makes your audience think you are a good writer? I’ve spent years investigating what makes an audience believe a person is a good writer. I’ve found it comes down to four equally important things: purpose, clarity, coherence, and style. At Prompt, we call these four items our “Framework for Good Writing.” Below, we cover the framework from a business, academic, or personal perspective. The framework also applies to narrative and creative writing, but we’ll not focus on these linkages here.

A Framework for Good Writing

Writing skills are a prerequisite for critical thinking (see my essay Writing is the Gateway to Critical Thinking). As such, the Framework for Good Writing we use at Prompt interlinks with many critical thinking skills (e.g., clarity and coherence).

The four components of good writing are intertwined – you need all to be a good writer. For example, it’s difficult to meet the bar for coherence without clarity and purpose. A writer with strong purpose, clarity, and coherence can still fail without a good style by leaving the audience bored and with a wandering mind. Below, we discuss the four components.

Purpose

Why are you writing? What idea are you hoping to communicate? What are you trying to achieve? The purpose is the first stage gate for being perceived as intelligent and competent. Paul Graham, the founder of Y Combinator, the world’s premier startup accelerator, puts it well in his essay How to Write Usefully: “Useful writing tells people something true and important that they didn't already know, and tells them as unequivocally as possible.”

I take it a step further. My writing aims to bring clear and structured thinking to a truth people may not know or may already believe (or are predisposed to believe) but cannot articulate well. Often, my audience may agree with my premise before reading, meaning they “already know” the truth; however, the audience finds value in my frameworks, language, perspectives, and evidence. My structures, not the overarching concept I’m writing about, are meant to be things Paul Graham refers to as “they didn’t already know,” and my language, reasoning, and evidence are meant to “tell them as unequivocally as possible.”

As a hypothetical example, you may have a good idea for your company. Nearly everyone is likely to agree your idea is interesting, and they may have thought of the idea themselves in the past. The purpose of your writing is not just to explain the idea but to convince your audience it is worth doing and describe how the idea should be executed.

In this essay, my purpose is to provide a common language for understanding what makes a writer good. Many people probably have some semblance of what makes writing good, but they struggle to articulate it well in a clear, cohesive argument. My writing is telling you some information you may already believe to be true, but it is presenting information in a clear, cohesive argument that gives you a framework and language to use when discussing what makes a good writer. Without a clearly defined purpose, my audience would struggle to perceive me as intelligent and competent. They would be left thinking, “what is the point?” and “how is this relevant?” instead of “this makes sense” and “I’m going to use this.”

Clarity

Clarity is the ability to clearly express one’s ideas and thoughts in writing the audience can easily understand. Clarity is hard. Give 10 people the same thing to read, and there could be 10 different interpretations. It’s nearly impossible to write something that every person understands in the same way. People have different life experiences, background knowledge, and thoughts they bring to everything they read. Said another way, clarity is on a spectrum. The lower the variability in interpretation, the clearer the writing.

I define the variability in interpretation as the distance between what the author truly meant and how the intended audience interpreted it. For example, low variability would be everyone in the audience identifying the same or similar purpose/main point and pulling out similar supporting facts. High variability is when the purpose/main point varies widely among the audience. The highest variability occurs when every audience member interprets the meaning as the complete opposite of the author’s intent.

Clarity matters because a lack of it breeds confusion and misinterpretation. And, confusion and misinterpretation create conflict, slows the speed at which things get done, and results in the dismissal of great ideas. Clear writing signals intelligence and competence. It gets everyone on the same page, thereby increasing the speed at which things get done and resulting in executing against great ideas.

Coherence

Coherence is the ability to clearly and logically connect ideas to create a unified argument or thought. Coherent writing allows an audience to easily and clearly follow and interpret the author’s thoughts without finding unsupported or extraneous claims or significant gaps in logic.

Like clarity, coherence can be difficult because people bring different life experiences, background knowledge, and perspectives to everything they read. As such, an audience may perceive gaps in logic that the author may not believe are there. However, the audience is always right. A confused or dissenting audience will perceive the writer as not intelligent or incompetent.

Writing coherently seeks to mitigate confusion and often persuades the audience to the writer’s point of view. The writer can identify and address potential gaps in their thinking. They can string together complex thoughts in support of a unifying idea or argument by logically supporting claims with the proper and accurate use of evidence. They can flexibly identify, synthesize, and accurately use sources. They can anticipate and attend to their audience’s background knowledge and perspectives. They can integrate additional information and thoughts from beyond or deeper within the subject at hand to both better frame the argument within a broader whole and provide the detail necessary to better support their thoughts.

Style

Style is the way a writer writes. Good writers have an engaging style. They leave you wanting to read more. They have you leaning in from start to finish, agreeing with each successive point. Here are some of the more important components of style.

Syntactical Fluency. This fancy-sounding term just means to vary your sentence structures. Varying sentence structures makes your writing more engaging and enjoyable. You should vary sentence length. Vary subjects, verbs, and predicates. Make use of synonyms instead of using the same word over and over. Place prepositional phrases in different locations. Syntactical fluency is a difficult skill to build. I often find myself reading for opportunities to improve my sentence variability when I’m revising.

Readability. Readability is the ease with which your audience can read your words and sentences. Ease matters because you don’t want your audience to need to work to understand what you’re trying to say. The more work you put on your audience, the more likely it is that they’ll be confused. Most readability measures use sentence length and word length – the longer, the harder it is to read. However, there are other considerations such as prepositional phrase use, like this phrase in the middle of a sentence, that can make reading a given sentence much more difficult.

Cohesion. Cohesion is the flow of your writing. It’s the connective tissue across paragraphs and between sentences that make it easier for your reader to understand the points you are making. At a lower level, cohesion is the connecting words between sentences. At a higher level, cohesion requires beginning paragraphs and sentences with information familiar to readers and then ending with information readers may not anticipate. Put simply, your audience prefers to start with what’s easy and familiar before getting to what’s hard and complex.

Anecdotes. Anecdotes are stories with a point. Stories resonate with people and make important points you’re making clearer. Often these are qualitative examples that serve as supporting evidence to an important point (that may be quantitative). People remember anecdotes, and anecdotes often serve as talking points for fully forming how an idea will work in practice.

Vocabulary. Vocabulary usage is often associated with intelligence. However, it can be a double-edged sword. Misuse a word, and people may perceive you as a poor writer, discounting the rest of your work. Use a word that’s unknown to your audience, and your audience may struggle to understand you. My general strategy is to keep my vocabulary simple. Occasionally, I use more complex words if they pop into my head while I’m writing. However, I almost always look the word up to make sure I’m using it correctly, and I think about whether my audience will know it or at least be able to understand it within the context of the writing.

Grammar Mechanics. I saved grammar until the end because I dislike the extreme importance some people give to it. Grammar is just a common set of rules that exist to make it possible to understand each other. A minor grammatical error is unlikely to decrease someone’s comprehension of the writing. However, many people are sticklers for grammar. Poor grammar is one of the quickest ways to lose an audience, meaning they’ll perceive you as not intelligent and incompetent, even if the rest of the writing is great. As such, it’s often critical to get grammar right – you cannot assume your audience does not care. Always take extra care to consider grammar when revising your work.

Implications for your writing

Being a good writer requires your audience to perceive you as a good writer. They need to perceive you as intelligent and competent. As you plan, write, and revise, make sure you’re considering the four interconnected components of good writing: purpose, clarity, coherence, and style. Keep in mind, you must attend to your audience’s perspectives (a topic for another day), as they matter more than you. Your audience decides if your writing is clear. Your audience decides if your writing makes logical sense. Keep your audience engaged and win them over to your thinking. Only then will you be a good writer.

Make sure you subscribe to The Writing Times (if you have not done so already). Also, share this issue with your friends, colleagues, and acquaintances.