Learning Through Writing

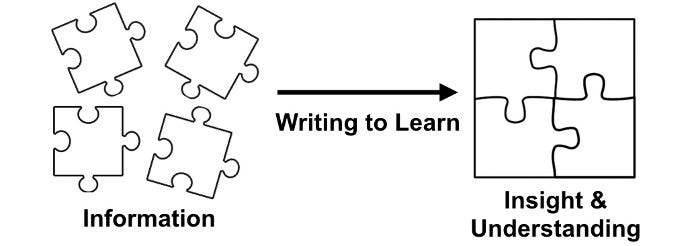

Writing is an integral part of learning. Learning requires understanding. Understanding requires people to build connections between their own thoughts and source information. Writing, being structured thinking, is the best connection between information and generating insight and understanding. I and many others in education refer to this connection as Writing to Learn.

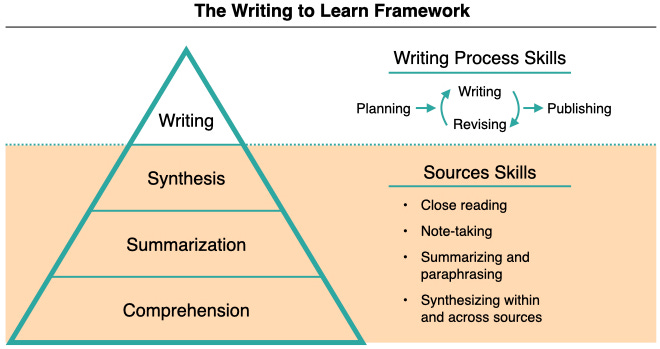

Writing to Learn is a complex skillset. It’s one part the writing process, another part using sources, and another part critical thinking. It’s also the most important skillset for learning and developing your thoughts on any topic.

This essay aims to posit Prompt’s Writing to Learn Framework that distills the skills required to be an effective writer and thereby critical thinker. But first, I start by reflecting on my learning and critical thinking process as I developed the Writing to Learn Framework. My reflection will help clarify writing’s central role in developing thought.

My Writing to Learn Experience

Over the past year, I’ve spent hundreds of hours learning and thinking about writing instruction. My journey started by realizing that my company, Prompt, needed to solve writing instruction before, during, and after writing to achieve our mission of making people better writers. Prompt started as a writing feedback company, providing feedback only after people wrote a draft. Yet, we often found the students and people we worked with missed the mark with their first drafts – they didn’t understand the goals of their writing (e.g., what their audience was looking for), struggled to create a cohesive argument, often didn’t accurately use supporting evidence, and were unable to identify gaps in their logic. As such, the feedback we provided often required a person to start over and work from the scaffolding we provided.

Like all good learners, writers, and thinkers, I started my learning journey with a set of questions I set out to answer (i.e., my learning goals).

What are the best ways to teach writing?

Are these methods being used in the classroom? If not, why?

How can I scale providing high-quality writing instruction?

Then, I sought information. In particular, I focused on finding syntheses of evidence-based interventions and instruction methodologies. One book I found particularly useful was The Best Practices in Writing Instruction, Third Edition, as it was written and edited by prominent writing researchers and synthesized the findings of hundreds of studies and interventions.¹

Then, I went through a learning process by engaging with the source materials. I’ve outlined my learning process in the diagram below and the description that follows.

Information Building Blocks. I studied and annotated sources as these form the evidence to support synthesized thoughts.

Moving from Annotation to Synthesis. When I had a particularly revelatory annotation, I jumped to synthesis by combining my new thought with previous thoughts and other information while attending to my learning goals.

Thought Creation. As I created thoughts, I evaluated them and determined what the next steps should be – e.g., Did I need to gather more information? Did I need to improve my logic? Was it time to start crystallizing my thoughts in writing?

Crystallize Thoughts in Writing. Once I felt good about a thought, I wanted to flesh it out in more structured writing. This helped me crystallize my thoughts and identify gaps in my logic and arguments, which led me to reflect on my ideas – e.g., Was my synthesis an accurate portrayal of the information? Were there other questions or ideas that arose that I needed to go back to source materials to answer or evaluate?

The act of writing was the critical part of the learning process. I wrote when I annotated. I wrote when I synthesized and evaluated my thoughts. I wrote when I combined multiple thoughts. I wrote when I identified gaps in my reasoning. I wrote hundreds of pages of annotated notes, syntheses of sources, syntheses across sources, and finally, a distillation of all of my thoughts into a single, coherent, and cohesive document on Prompt’s approach to writing instruction.

Prompt’s Writing to Learn Framework

My synthesis of evidence-based writing instruction methods pointed to Writing to Learn as the key concept for improving writing outcomes. Engaging with writing researchers cemented my belief. When I refer to writing as a Gateway Skill to critical thinking and problem solving, I am referring to the Writing to Learn skillset; learning and thinking are synonymous with writing in the creation of new ideas and knowledge.

So, let’s more clearly define Writing to Learn. Writing to Learn is the skillset people use to generate insight and understanding from a vast array of information sources. Writing to Learn is a generalizable, transferable, goal-oriented skillset people can apply independently to any subject or topic. Without writing to learn skills, students cannot succeed in the classroom, and professionals cannot succeed in the workplace.

Unfortunately, most people struggle with Writing to Learn. They are unable to generate insight and understanding from information sources because they lack the foundational reading comprehension, summarization, synthesis, and writing planning skills.¹ I created the Writing to Learn Framework to better visualize the skills required to be effective writers and learners.

The framework matches well with the research and my learning process I outlined above. First and foremost, people need sources skills. They need to be able to comprehend what they read by identifying and accurately using information. They need to be able to summarize what they’ve read as summarization forms the Building Blocks of evidence for supporting an argument. They then need to be able to synthesize information within and across sources – the core component of Thought Creation. Once a person has a sources skills foundation, they are able to write from sources by going through the writing process to Crystallize Thoughts in Writing.

Concluding thoughts

Our education system fails to teach Writing to Learn. It’s why critical thinking and problem solving are such valued and rare skills. Many people are unable to answer questions about what they read in a text. Many are unable to accurately summarize what they read. Many are unable to synthesize a source or across sources. Without sources skills, it’s difficult to learn something new or develop a coherent set of thoughts on a topic. As such, many people struggle to matriculate and persist in postsecondary education, and my analysis indicates only 1 in 10 people exit our education system (K-12 and higher ed) with adequate writing skills for the workforce.

Circling back to my three learning goals, I believe I now have answers for all. First, there are a clear set of best practices for teaching and improving writing. Second, these methods are not being used in the classroom because teaching Writing to Learn is complex, mentally-taxing, and time-consuming. Third, it is possible to scale providing high-quality writing instruction for K-12, higher ed, and professionals.

That’s enough for now. There is a LOT to cover in future posts on how to tactically implement Writing to Learn at scale – something we’re actively working on at Prompt. However, I’ll leave you with a quick thought exercise I recommend doing – reflect on your own learning process and how you create and structure your thoughts. When do you write? What do you write? How do you use writing to generate the outcome you desire? Then, reflect on your perceptions of how other people you know well learn and structure their thoughts. Do you believe their process is effective?... I bet you often find yourself spotting seemingly obvious logic gaps – a signal that they need to improve their writing to learn skills.

If you’re not a subscriber, please subscribe now to get my weekly newsletter. If you enjoyed this essay, please share it with others who will find it valuable.

¹ Graham, S., MacArthur C. A., & Herbert, M. (Eds.). (2018). Best Practices in Writing Instruction, Third Edition. The Guilford Press.